Increasing Your Exposure—Studio Safety for Professional Artists

Simon Bland: 31 Mar 2024

Did you ever wonder if there was a single thing that could differentiate professional artists from amateur artists? Apart from the getting paid part, of course, which I assure you is not much of a differentiator.

One of the most significant differences between painting as an amateur/occasional painter and painting professionally/full-time is the amount of exposure you have to your art materials. There is a full order of magnitude of increase, enough that it requires the professional painter to exercise extra care to keep themselves and others from harm.

You hear the words “toxic” and “toxicity” thrown around in the art world. These terms apply to some commonly used art materials which can significantly affect your health with long term use. Yet, most artists begin working with little understanding or awareness of materials safety.

In this article I just want to focus on oil painting, but there are similar concerns in pastel painting, watercolor, sculpture, modelling, and almost every other area of the art world. I don’t feel well enough informed to write about those other topics, so I would encourage you to seek out more information elsewhere.

There are three main areas of concern for oil painters.

Risk #1: Exposure to Heavy Metals

Artists’ materials were exempted from the strict regulations that cover the manufacture and sale of paint in the US—the reason being that household and industrial paint is produced in amounts that far exceed those of artists’ paint. Major art brands have tried to push safer alternatives, but we pesky artists have always demanded our traditionally unsafe products. Boutique brands have also entered the market to fill niche gaps in supply.

Although almost all pigments in oil paint are safer now than they have ever been in the past, some paints still contain compounds that can cause a variety of diseases, including types of cancer. Even so, these paints can be used safely providing you don’t ingest them or get paint dust in your lungs, however there is a risk of doing just that whenever you have exposure to them. You also pose a risk to others around you.

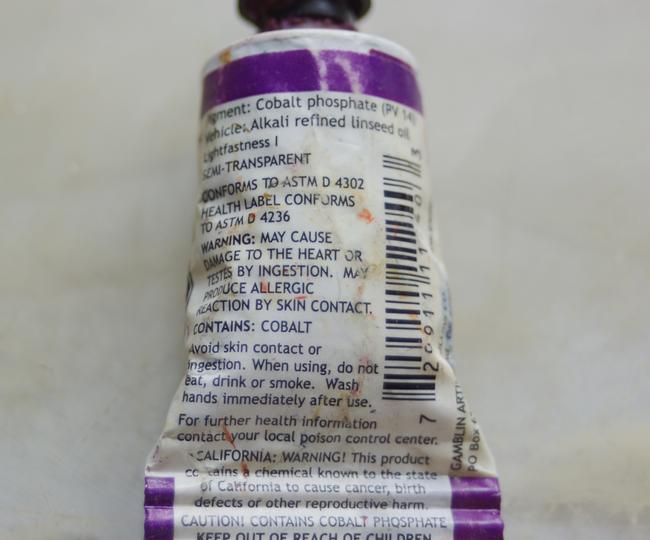

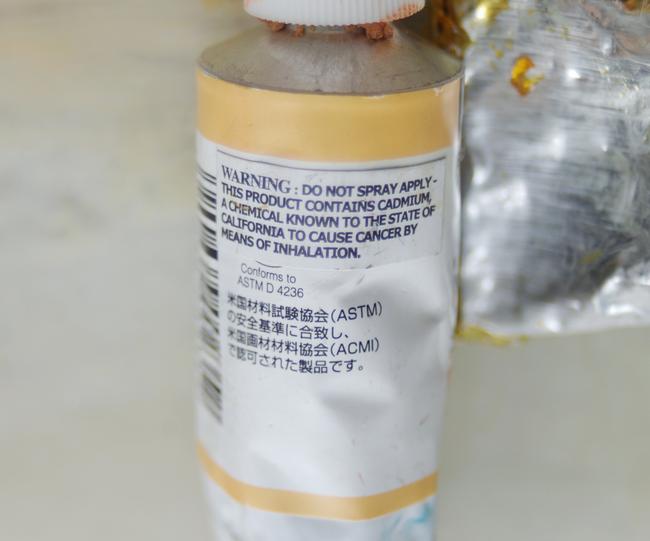

The most concerning of these ingredients is lead (as lead carbonate), but other heavy metals, including cadmium, cobalt, and manganese can pose a potential risk to health. The actual risk to you of using these products can vary greatly depending on the formulation of the pigment: for example, cobalt blue (cobalt oxide—aluminum oxide, PB28) is considered safe, cobalt violet (cobalt phosphate, PV14) is unsafe if you are careless with it.

It's really important to check the labels on your tubes of paint before use.

Fortunately, those pigments which cause acute toxicity—those containing mercury and arsenic, for example—have been almost entirely replaced with safer alternatives.

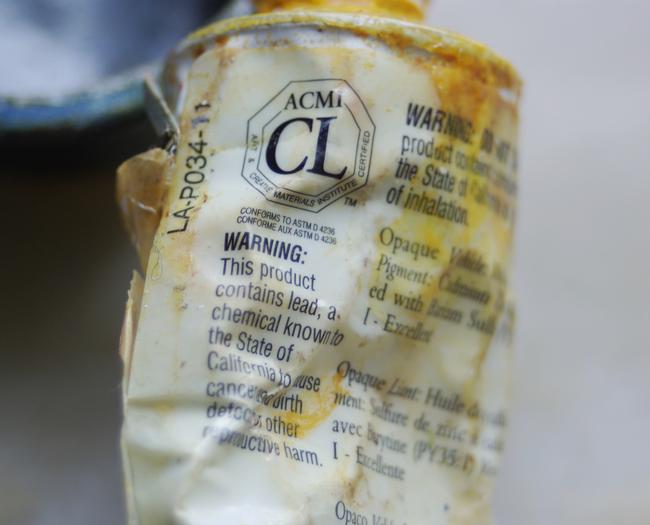

Labelling can be confusing, because there are usually different types of labelling applied (three in the US, at least). The one you are most likely to see and ignore is "Conforms to ASTM D 4236". This means that the labelling on the tube conforms to a set of standards laid down for labelling chronic health hazards and has nothing to do with the product itself.

Unfortunately, I can only talk about health labelling in the US, however I suspect that EU regulations about sale and labelling of artists’ materials are stricter. My major gripe with artist’s products is that while safety labelling is sometimes comprehensive, some products can be labelled as unsafe without any indication why. On top of that, some labels are not well designed (they not self-explanatory) and are difficult to understand without some prior research.

In the US, there are two labels you need to be aware of. The first of these is the ACMI label. This comes in two flavors: the Approved Product (AP) label, which indicates that a product is safe to use, and the Cautionary Label (CL), which indicates that precautions must be taken for the product to be used safely (i.e., it is actually not entirely safe to use). You can find out more at the The Art and Creative Materials Institute, Inc. (acmiart.org).

An ACMI Approved Product (AP) label indicates that the product is considered safe.

The second type of labelling in the US is California’s Prop. 65 labelling. It is mandatory for all products sold in California which contain an ingredient that can cause cancer or developmental harm to carry this label (since California is such a large market, all US products generally have this label). The label will also list the problematic ingredient.

Here a California Prop 65 label has been applied over the top of the ACMI "CL" label.

See the end of the article for some other examples of health labelling on paints.

For working with oil paint, I would recommend the following minimum safely guidelines (sorry that there are so many). These should help to mitigate the risks, and I would recommend following them no matter which pigments you employ so that good habits become ingrained:

- Always wear protective gloves to paint (you can wear the same pair of gloves more than once).

- Build your core palette around paints labelled ACMI Approved Product (AP), even if you think they aren't as good as the real stuff. Limit your use of ACMI Cautionary Label (CL) or California Prop. 65 labelled paints.

- Don’t use paint that contains lead carbonate, i.e. Lead White, Flake White, Cremnitz White. Unless you are in the business of restoring old masters, there's no reason to use it.

- Don’t sand down old paintings except where you know it is safe to do so. In general, you should not sand down any paint that contains heavy metals.

- Don’t eat or drink in your studio or put brushes in your mouth.

- Don’t wash your brushes in a place where you prepare food.

- Wear an apron, or wear “painting clothes” that you don’t wear around your home.

- Don’t let children use or play with anything marked with the ACMI Cautionary Label (CL) or California Prop. 65 labels.

And one final precaution which will only apply to a very few:

- Don’t attempt to grind your own paint unless you absolutely must and have the training and equipment (air filtration, masks) to do it safely.

When you start painting, you will want to improve the quality of your work and you will get the idea that using the same paints as your favorite artist will make your paintings more like theirs. It’s an utterly ridiculous notion, but every artist I’ve known, including myself, has fallen into this trap to some degree.

To give an actual example of this: I have been in art classes with amateur artists who were using lead white paint and were encouraged to do so by the instructor. It's an unbelievably stupid thing to do—there's literally no scenario in which that was justified—and all that exposure was incurred for nothing.

Risk #2: Exposure to Petroleum Distillates and other VOCs (volatile organic compounds)

Another source of things that cause cancer or developmental harm are the solvents that we use.

Experiencing the smell of true mineral spirits will be enough to convince you that the fumes are not safe to breathe. My concern with using odorless mineral spirits (OMS) is that the lack of smell lulls you into a false sense of security. I know it’s better to use OMS than regular mineral spirits, but the product still evaporates into your studio’s atmosphere. If you can’t smell it, you might not realize you absolutely must ventilate the room during use.

A reminder, in case you need it, that what is being evaporated is the actual solvent. When you breathe in solvent fumes, you are taking the same solvent that was in the can into your lungs, and it has the potential to get into your bloodstream.

The health concerns related to petroleum distillate and VOC exposure are different from those of your paint pigments. In this case, cancer and neurological damage are the primary hazards. Ingestion in quantity can be fatal.

Exposure through inhalation is the main route of concern for adult users and these products can cause significant skin irritation and severe eye damage on contact. You can also develop allergies to painting solvents.

Again, ACMI and California Prop. 65 labelling apply. You’ll find the ACMI Cautionary Label on a lot of products that you might think completely safe at first glance, such as Liquin and Oil Painting Varnish.

The ACMI Cautionary Label on a bottle of Liquin.

I looked for a safer alternative for a very long time and I settled on d-limonene as my everyday solvent. It is derived from the rind of oranges and is used in lots of cleaning products. It is even considered food safe.

Still, it produces plenty of fumes and it brings other risks such as potential flammability. It's firmly in the ACMI CL label territory. To reduce the risks, I just use a small quantity of d-limonene in a lidded jar that I dip my brushes in to clean. I also make sure to put any used paper towels in my lidded metal can, along with the paint rags. Overall, I use much less than I ever did when I used OMS as my primary solvent.

Other plant-derived solvents like lavender oil (oil of spike) and artists' grade turpentine are also available. They come with the same kind of environmental and health concerns as d-limonene, so always use them with an abundance of caution.

In the end, your decision about what solvent to use will often come down to what you and your wallet can best tolerate.

A much safer alternative is to use water mixable oils with water-mixable, solvent free mediums. I started out this way, by necessity rather than by choice, and I eventually progressed to regular oils. It helped me go through a long period of learning to use oil paints in complete safety. I would encourage you to do the same, if possible.

If you must work with solvents, I recommend:

- Ventilating your studio as much as possible.

- Avoid using mineral spirits (even odorless) if you can – look for other alternatives. Yes, this is very hard to do and unfortunately, it gets expensive very quickly.

- Keep a lid on your solvents when not in use and don’t leave a brush washer open.

- Stick with water mixable oils if possible.

- Be aware that some mediums also contain petroleum distillates. Choose solvent free mediums whenever available.

Risk #3: Fire Hazards

I’m certain that this is a rare problem, yet I know of at least one professional oil painter who has experienced a studio fire.

Lots of the stuff you use in a studio is flammable. In addition, drying oils like linseed, safflower, and walnut react with oxygen to harden. This gives off heat and other chemical byproducts (including hydrogen peroxide which is also highly flammable).

If you get enough oil on some rags (or paper towel) and ball them up, you can potentially start a fire.

All oil solvents are flammable to varying degrees. They should never be exposed to flame or kept near a heater.

The combination of oil paint, paper towels and solvents, therefore, is an accident waiting to happen. The only safe way to deal with your studio trash is to put it in a metal can that has a lid on it. You should also have a fire extinguisher for your studio.

Examples of Health Labelling on Paints

Here are some examples of the labelling on some other tubes of paint and mediums that I have laying around.

Your standard/base palette of colors should have ACMI AP labels.

Lead is not included on the list of pigments but appears in the California Prop 65 warning.

Occasionally, you will see a lead warning on paint where lead is not listed in the ingredients. The source of the problem always seems to be some zinc content in the paint. Since zinc and lead are almost always mined together, there may be the potential for some cross contamination of the pigment.

A second California Prop 65 warning on the same tube for a different ingredient

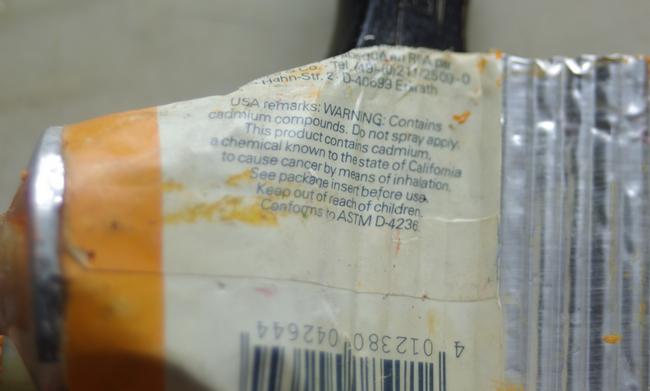

You may be wondering why artists would want to use a pigment like cadmium yellow when there are safe alternatives available. Some of the reasons are that the non-toxic yellow pigments tend to have either lower tinting strength, are more transparent, or have a slightly "off" hue.

You can work around all of these things, but sometimes it's easier just to keep a tube of the nasty stuff to one side for special occasions when you need a yellow that will do the job straight out of the tube.

Details are sometimes hidden in small print.

This is tube of cadmium yellow deep. Unlike cadmium yellow, this is not a terribly useful pigment to have in your studio, and you can mix it from other colors fairly easily.

Other less useful cadmiums include the red and scarlet pigments. I find that non-toxic pigments like W&N's Bright Red are much better.

Some Final Remarks

We've explored some of the risks that increase when you start to paint full time, especially exposure to heavy metals, exposure to VOCs, and fire hazards. There are things you can do to mitigate each of these risks.

But can we quantify the actual risk? I've been unable to find many recent studies which do this.

Overall lifespan may not be much affected according to this 2013 study, however the source is Russian, a country where life expectancy is markedly lower than the US. An increased cancer rate among professional artists is found in this 1985 study and in this 1986 study. The good news is that the latter studies were done nearly 40 years ago and would have included artists who had been painting at a time when it was not unusual to use lead white while smoking in the studio.

The best protection is to take this subject seriously and utilize safe practices while in your studio. I hope that this article has provided some useful information that will help to do just that.

Simon Bland: 31 Mar 2024