What is Drawing?

Simon Bland: 28 Feb 2024

Everyone knows that picture made with a pencil and paper is called a drawing, whether it's a scaled technical drawing, a loose sketch, an architect’s rendering, or even a scribble. But what is the actual definition of drawing and what part does it play in painting?

In this blog post I go in search of answers to these questions and attempt to establish better understanding of drawing.

On first glance, this may seem like a waste of time—I know that even a child can make a drawing with a pencil and paper. In fact, you may be wondering why I’ve bothered to write about it.

You only need to search for the definition of drawing on Google to get a taste of the problem:

- A picture or diagram made with a pencil, pen, or crayon rather than paint. [1. Google’s own dictionary service]

- The art or technique of representing an object or outlining a figure, plan, or sketch by means of lines. [2. Merriam-Webster]

- Drawing is a visual art that uses an instrument to mark paper or another two-dimensional surface. The instrument might be pencils, crayons, pens with inks, brushes with paints, or combinations of these, and in more modern times, computer styluses with graphics tablets. [3. Wikipedia]

Something is going on here because none of these definitions agree with each other. Not only that, but there is also something slightly off with each one (see the footnotes). Why is that?

Resorting to books, I was surprised to find that John Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing (1857), a book about creating drawings, contained no definition of drawing. In fact, it wasn’t we reach the beginnings of the modern era and a search though Harold Speed's book on drawing that I found something useful:

- The expression of form upon a plane surface. [The Practice and Science of Drawing. Harold Speed. 1913]

By the way, this is an artist's definition. At a stretch, you could also apply it to things like technical drawing and architect's plans, however they really belong in their own class, and we shall omit them going forward.

This definition may be confusing because it doesn't use everyday language, but it has important implications. Let's demonstrate with some examples.

1. A Perspective Drawing

I got a small bowl from my kitchen to use as a still life prop.

The bowl I used is actually a small ramekin, seen here under window light.

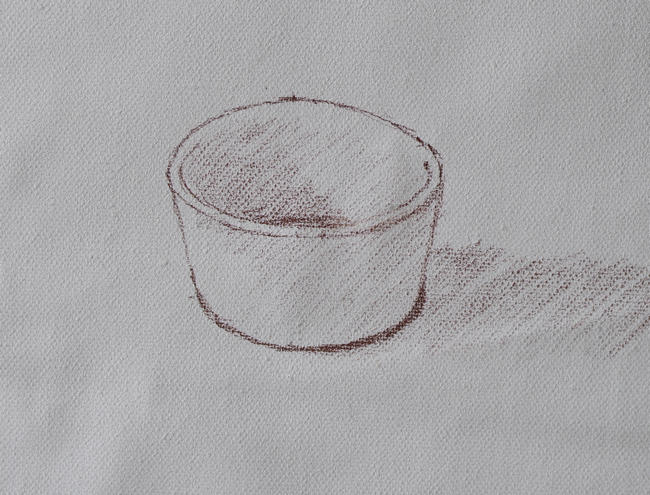

Suppose I make an image that represents the bowl on a piece of paper with a pencil. I do it so there is a correspondence between what I see and what I draw [4].

I start making lines with the pencil to create an outline which shows where all the perceived edges are [5]. It looks like the bowl and has the same perspective, although I scale it to make it a size that fits well on the paper, not necessarily the same size as it is in real life.

I may or may not add a little shading to emphasize the lights and darks, and three-dimensionality is implied, but does not need to be fully realized. I stop without fully rendering the surfaces [6].

Although I am out of practice, the result is a crude drawing. I have created an expression of a solid object (the form) on a two-dimensional surface.

A drawing of the ramekin (graphite pencil on paper)

We use drawing as both a noun, to describe the picture in front of us, and a verb, to describe the process of creating it, so why would we have a problem with something so straightforward?

Let’s look at it in the context of painting... [7].

2. Drawing as part of painting

Suppose I make another drawing of the bowl just as I did before, except that I now use Conte crayon on a piece of canvas. I take care of edges, shapes, proportion, scale, and position. I add a little shading to emphasize the lights and darks.

I have created a drawing on the canvas, albeit another crude one.

Another drawing of the ramekin (pastel pencil on canvas)

Then I start to add layers of paint over the top of the drawing on the canvas.

Oil paint applied over the top of the crayon drawing.

Now my question is: what has happened to the drawing?

Your first thought might be, “it disappeared under the paint”, but I think you’ll agree that the core of the crayon drawing has remained. Things like the lines, shapes, edges, proportion, scale, and composition still exist — it’s just that they now appear in paint. Some lines might be the result of pushing areas of paint against each other, but they are there all the same.

What we refer to as drawing, then, is something more than just an image in pencil or charcoal. It is describing some set of properties of that image that persist through to the painting. In this example, drawing defines the structures and shapes, perspective, proportion, scale, and composition.

So, when we see a painting and say, “good drawing”, we mean that the lines, shapes, edges, etc. show good draftsmanship or technical skill. The form is expressed in the layers of paint.

3. Transition from drawing to painting

Now for another thought experiment. Suppose that we start yet another painting of the same bowl on canvas, but this time we do the drawing in thinned paint. Note that the lines are much thicker than before, even though I used a reasonably small round brush.

The same drawing done in paint (oil paint on canvas)

As before, we add layers of paint over the top of the drawing.

Oil paint applied over the top of the layout (oil on canvas)

My question is, where does the separation point between drawing and painting lie?

In the first example we used a change of medium to separate the two actions. Now we don’t change medium, so is there still a point at which the transition from drawing to painting occurs?

It's easy to think of a case where you can clearly separate drawing and painting—a paint-by-numbers, for example where you must fill in the predefined shapes with paint. But in this example, we have created our own initial layout drawing and we have continued to refine the drawing all the way through to the finish line.

I would argue then that, instead of two processes happening one after the other, they overlap and are basically inseparable.

In my world, painting is also an act of drawing. I'll demonstrate that in the next example.

4. When drawing is implied

Now we return to the bowl for a final time, and we consider the case where we produce the same painting directly, without a charcoal or paint drawing underneath.

I started this version of the painting by massing in the ramekin (oil on canvas)

With the bowl massed in, I paint the bowl directly over the top. There are no explicit lines used in the construction of the form.

A third version of the ramekin done without an underlying drawing (oil on canvas)

This painting has the same structure, proportion, perspective, scale, and composition, as our previous efforts and therefore the same drawing (using my definition above), but at no point is an actual drawing done (in the sense of our original definitions).

The drawing has occurred entirely within the painting process. It is seen in the abstract representation of lines, edges, shapes, proportion, perspective, scale, and composition of the painting.

Conclusion

We progressed from thinking of a drawing as images in pencil on paper, to one where we see drawing as an idea that is contained in a representative image.

The drawing process is the creation of structure, proportion, perspective, scale, and composition in imagery on surfaces, irrespective of the method used. In the words of Harold Speed, it is an expression of form upon a plane surface.

We also understand that drawing and painting are not analogs of each other: they are not the same thing being done in different mediums.

Footnotes

[1] You can also draw in a fluid medium like ink or even in paint.

[2] The definition of using lines is also consistent with John Ruskin’s work, but it is fundamentally flawed as we demonstrate in the article.

[3] Despite being the longest definition, it’s so vague that it’s not really giving us a definition of anything.

[4] Drawing something “as we see it” here means using the ideas and conventions of realism in post-renaissance Western Art. Other cultures at other periods in time might interpret the drawing process entirely differently.

[5] All drawing is, in part, symbolic and follows some kind of convention. The most obvious way you see this is in the way we use lines as an abstract way to symbolize edges—we create an outline around shapes to make them recognizable. However, these lines do not exist in real life.

[6] We render a surface to make it look solid or three dimensional. We might use the term “rendering” to describe an illustration that helps you to visualize an object. For example, architectural renderings are drawings which show you how a planned building will appear in real life.

[7] I am using the term “painting” to refer to any process that uses a pigment/medium mixture which is applied in a series of marks and/or fluid washes. Thus, the medium could be oil paint, ink, watercolor, or even a dry medium like pastel.

Simon Bland: 28 Feb 2024